Down the pit

A look at the history of Chesterfield's mining industries and the lives of the miners.

Twentieth century coal

In the early decades of the twentieth century coal mining changed very little compared to the Victorian period. Mines were privately owned and methods and equipment largely remained the same. Coal also continued to be Britain’s main energy source.

However, the 1920s and 1930s were a time of national economic depression and the coal industry struggled. Problems and disputes relating to increasing costs, productivity and the need for modernisation paved the way for the nationalisation of the coal mines in 1947, bringing them under government control. Collieries in Derbyshire became part of the East Midlands Division of the National Coal Board.

In the later twentieth century, as coal’s use in energy production declined, pits began to be closed. Parkhouse Colliery closed in 1962, Holmewood Colliery in 1968 and Williamthorpe in 1970. The 1980s saw widespread mine closures and Markham Colliery was one of the last in the local area to close in 1993.

The coal industry declined substantially during the second half of the twentieth century. Markham Colliery (pictured above in 1995) was one of the last deep mines in Derbyshire to stop production in 1993. It was the largest pit in the area employing over 1,000 miners in 1992. Bolsover Colliery also closed in 1993.

The closure of the coal mines not only effected unemployment and local communities but also the landscape as the former spoil heaps remained. The Ireland Colliery site in Staveley was transformed into Poolsbrook Country Park (shown above) in 1997 was part of a reclamation scheme. The former Markham Colliery site is now Markham Vale business park.

During both world wars the demand for coal was high however many skilled miners joined the Forces or were part of the territorial army and called up. During WWII, due to the lack of miners, men were conscripted into the mines (Bevin Boys).

Nationalisation in 1947 was a major undertaking. 958 collieries were acquired and over £200 million paid in compensation to mine owners. The National Coal Board was a public corporation formed to manage the industry. In 1987, it became British Coal.

Growth of an industry

Coal had been mined in the Chesterfield area for centuries and was an important fuel for local industries. It was not until the late eighteenth century, however, that the industry really began to take off. The development of good transport links, beginning with the canal in 1777 and later the building of the railways, enabled the industry to prosper.

The discovery of ironstone was an important factor in the coal industry’s growth. Both coal and iron were increasingly in demand for building railways, ships and steam engines. By the 1850s, larger companies at Clay Cross, Sheepbridge and Staveley were established combining the two industries.

By the end of the nineteenth century, as shallower seams were worked out, improved technology enabled coal to be mined at ever greater depths.

George Stephenson is one of Chesterfield’s most famous residents. During the building of the North Midland Railway from Derby to Leeds, coal seams were found while cutting the tunnel at Clay Cross. Stephenson founded the Clay Cross Colliery Company in 1837 as a result. This transformed the small village, trebling its population by 1840.

Men, women and children worked underground in the coal mines in the early nineteenth century. Children could be as young as 5 years old. In 1842 females and boys under 10 years old were no longer allowed to work down the pit. This led to hardship in many families as it led to loss of wages.

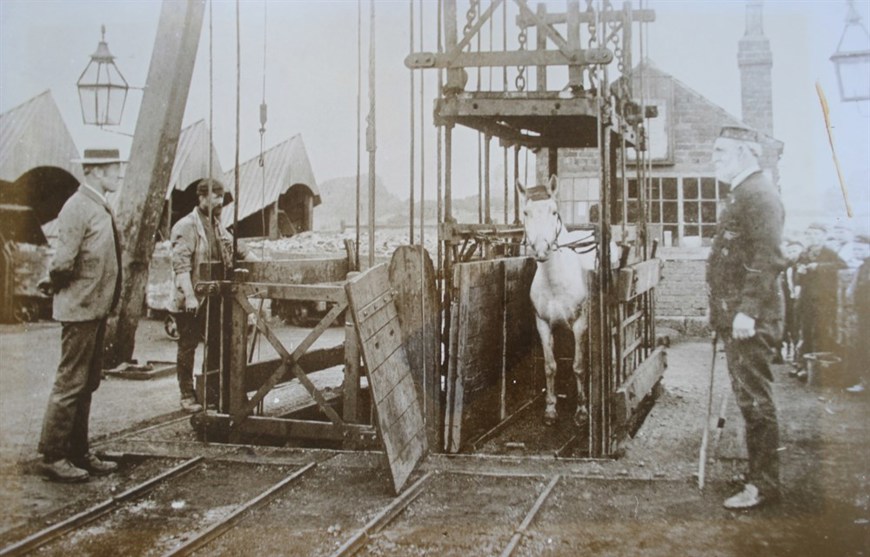

Horses replaced women in transporting the coal underground. They were an expensive addition to the workforce as they needed feeding and the underground roadways needed to be made bigger to allow the horses to travel. They spent their lives underground but were generally well treated.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the larger collieries were a complex of structures: engines for winding and pumping, ventilation fans and screening areas for coal. The pit head winding gear, initially with frames built in timber and later iron and steel, became the iconic symbol of mining in the landscape.

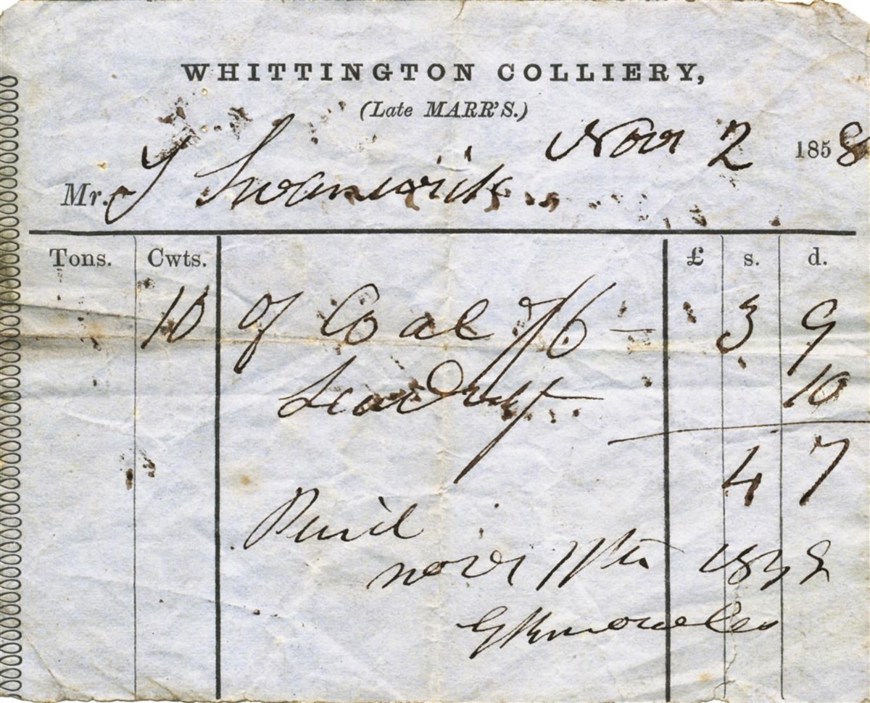

There were many collieries in Chesterfield in the Victorian period. They were mostly on a small scale but mines at Newbold, Ashgate, Boythorpe, Brampton and Whittington helped to provide vital fuel for the local industries such as the potteries.

Coal during the nineteenth century was extracted by hand. Picks and shovels were standard equipment for miners. Machines were being introduced by 1900 but they were slow to take off and mining was still done by hand in many places well into the twentieth century.

As the mining industry grew, so did the demand for workers. Mining was labour intensive and mine owners often needed to bring in workers from farther afield. Workmen’s trains were introduced by the Staveley Company in 1860 to bring workers from Chesterfield. The trains were known locally as ‘paddy mails’ due to the large number of Irishmen employed.

A dangerous job

Coal mining could be a very dangerous job. Injuries were common and miners worked with the constant risk of flooding, roofs collapsing and gas. In just a single year in the 1920s, 1,297 miners in Britain were killed at work and 212,256 were injured. Miners needed to extract the coal as quickly and safely as possible.

Miners also suffered from long term illnesses such as lung diseases from breathing in coal dust, sight problems and inflammation of the joints. The growth of mechanisation to extract coal in the twentieth century brought more health issues: hearing damage from noise and Vibration White Finger.

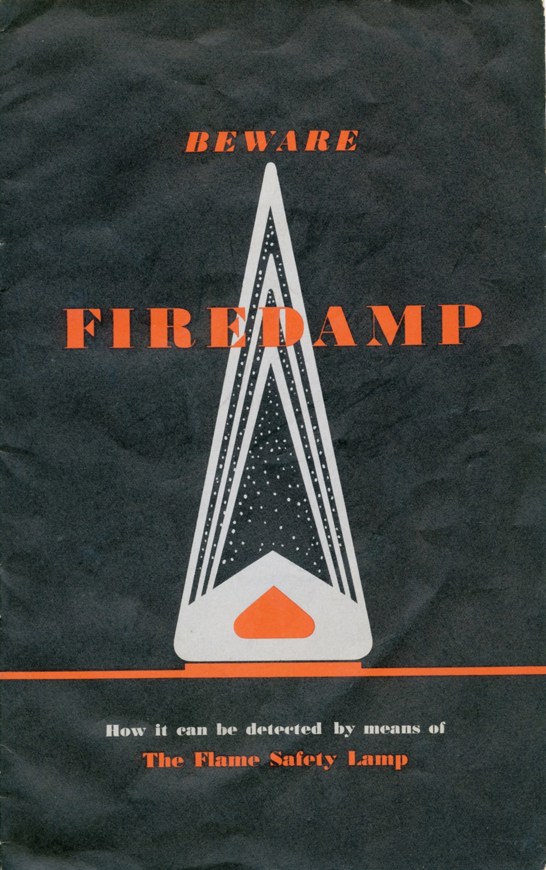

Miners’ safety lamps were developed in the nineteenth century to provide a safe form of lighting down the pit and indicate the presence of gas. Naked flames could cause gas explosions. Although safe electrical lamps for lighting were developed, some miners continued to use flame safety lamps to detect gas.

A build of gas in a mine is dangerous. Firedamp is methane gas contained naturally within the coal. It released when the coal is mined and can cause explosions. Underground safety became increasingly important and strict rules were in place restricting what could be taken down the mines. Smoking was strictly forbidden.

Mining disasters had a devastating effect on the local community. Many families worked together in the mines. In 1882, 45 men and boys died in an explosion at Parkhouse Colliery, Clay Cross. There was also a gas explosion at Markham Colliery in 1938 that killed 79 people. The Parkhouse disaster led to wider use of the safety lamp.

In the nineteenth century and early twentieth century, miners worked in poor light. They often suffered from an eye disease called Nystagmus which could lead to partial or total blindness. Dr Josiah Court worked in Staveley and was the consulting surgeon for the Derbyshire Miners’ Union. His work led to the link between poor lighting in mines and the disease.

The 1911 Coal Mines Act made the provision of rescue stations near each colliery compulsory. Each station was required to have men fully trained and equipped in case of an emergency. Chesterfield’s Rescue Station opened on Infirmary Road in 1918.

Miners had little protective equipment underground and it was not until the 1930s that safety helmets were introduced.

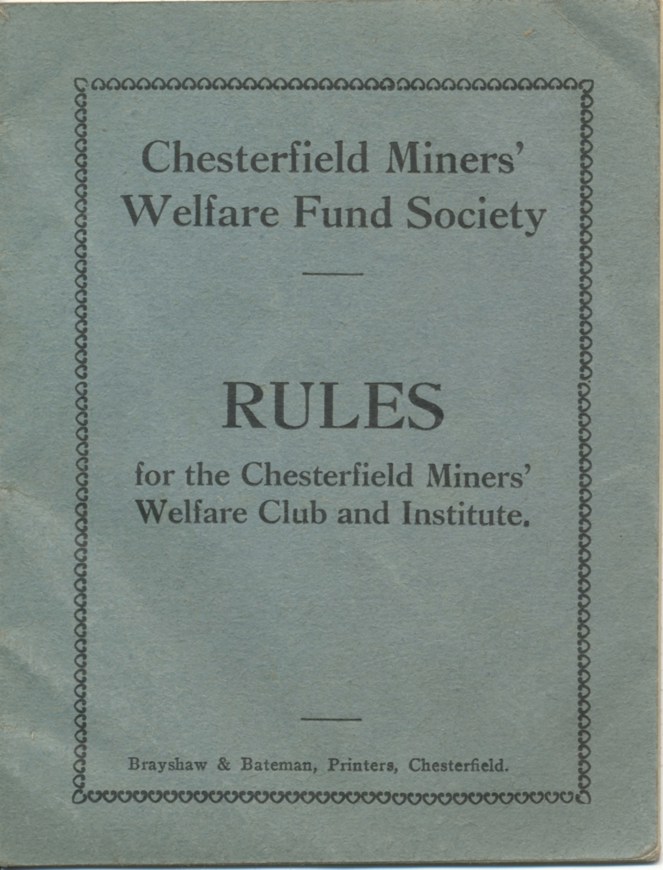

The Derbyshire Miners’ Convalescent Home at Skegness opened in 1928, paid for by the Miners’ Welfare Fund, for those recovering from injury. The Fund was set up as a result of the 1920 Mining Industry Act. Mine owners had to pay a levy towards the fund to provide baths, recreational facilities and health services.

A miner’s life

Coal mining was a dirty job and miners washed themselves at home well into the twentieth century. The Coal Mines Act of 1911 obliged coal owners to provide baths but it wasn’t until after 1926 when the Miners’ Welfare Fund began a fund to build baths that they took off. By 1952, 400 pit baths had been built in the UK.

Some coal owners provided housing for their workers and charged rent. The Clay Cross Company built 130 houses in the village in 1841 and the Staveley Company built houses in Barrow Hill in the 1850s.

Miners’ institutes or welfare halls were established from the 1920s onwards. They were places for educational, social and leisure activities and were generally built and run through a communal fund raised by the miners. They continue to be part of the local community today. Chesterfield’s Miners’ Welfare was established in 1926.

Working long hours underground, made leisure time precious. Gardening, sports such as football and cricket and music were an important part of community life. Ireland Colliery Brass Band began in the late nineteenth century and is still going strong today.

Before the nationalisation of coal mines in 1947, there were no standard rates of pay. Wages fluctuated with the demand for coal. Miners were usually paid a specified amount for each ton of coal extracted (piece-work).

The Derbyshire Miners Holiday Camp opened at Skegness in 1939 mainly funded by the Miners’ Welfare Fund. This enabled miners and their families to enjoy a week’s holiday at the seaside, many for the first time. It closed in the 1990s.

By the end of the nineteenth century, technical adult education was being offered to miners, encouraged by the Derbyshire Miners’ Association. Chesterfield was a centre for mining classes organised by the University of Sheffield. Following nationalisation in 1947, training and apprenticeship schemes were set up involving on-the-job training and classes at college.

Methodism, particularly Primitive Methodism, had a large influence amongst many local miners. Some of the early union leaders, such as William Harvey, were preachers.

Miners united

Joining together as a union to work towards better pay and working conditions was not an easy journey for coal miners. Early attempts made by miners to join unions were often met with opposition by their employers. In 1866 around 170 miners were laid off at Staveley and Clay Cross because of this.

Trade Unions, however, became increasingly established and were made legal in 1871. Miners from the Chesterfield area initially became members of the South Yorkshire Miners’ Association but it was felt that their views were not fully represented. The Derbyshire Miners’ Association was therefore founded in 1880 to represent miners in North Derbyshire.

The Union, becoming part of the National Union of Mineworkers in 1945, represented the local miners for over 125 years, working to protect their rights and improve all aspects of their working life.

These annual events strengthened support for the union and attracted large crowds. The first one, held in 1873, brought around 30,000 visitors to the town.

The Derbyshire Miners’ Association initially met at the Sun Inn in Chesterfield but they needed their own headquarters. The funds were raised through member subscription and events and the building opened in 1893 on Saltergate.

The two most influential figures in forming the Derbyshire Miners’ Association were James Harvey and William Haslam. Local miners, they worked for the Association for over 30 years increasing the membership from 696 in 1881 to over 42,000 in 1914. Their statues were unveiled on Saltergate in 1915 as a memorial to them.

One of the first large mining disputes regarded the pit owners wanting to issue a 25% reduction in wages. 300,000 miners were ‘locked out’ from June until November causing much hardship. The Derbyshire Miners’ Association mortgaged their new building to continue to provide strike pay.

Soup was distributed at New Whittington during the 1912 miners’ strike. This was the first national strike by miners and helped to establish a minimum wage. The strikes of 1926 and 1972 were also related to miners’ pay levels.

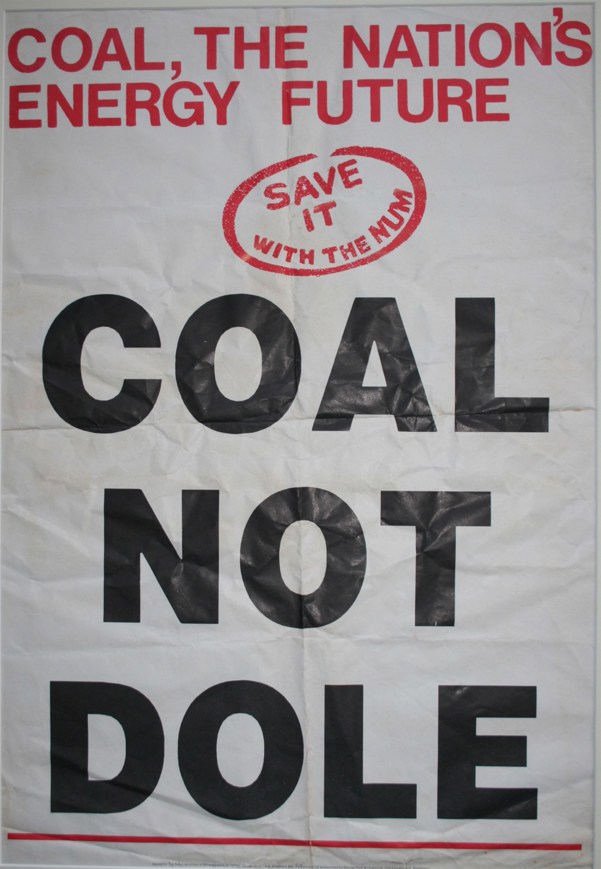

The 1980s was a difficult time for miners. It saw the government begin a policy of the closure of coal mines. Despite lobbying and negotiations, no agreement was reached and miners began industrial action in March 1984. Unfortunately the difficult year long strike did not halt the mine closures.